|

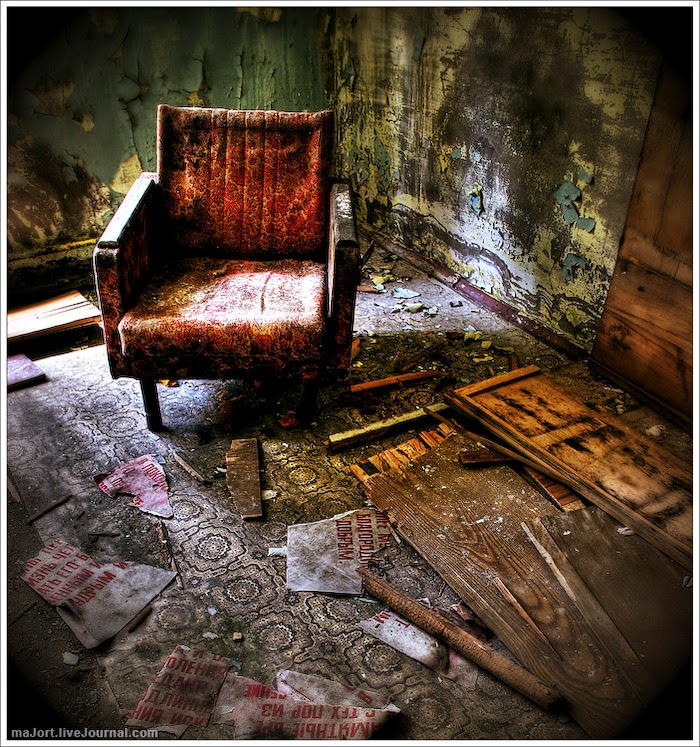

| Sisyphus by Franz Stuck |

Writers

spend long years arduously composing their literary works, then devote

themselves, in what is often a comparable length of time, to subsequent

revisions, edits, polishes, and scrubs until the fictional narrative emerges

from its literary washing sleekly pristine – or at least as best as we are able

to render it. In my limited experience, of both biological as well as literary

offspring, some dirt always lingers behind the ears in those hard-to-reach

places – which is when one brings in an incisive editor or an equally resolute

grandparent.

And

then? The progeny is freshly scrubbed to pinkness, attired in its Sunday best,

and presented to society, with the last-minute authorial effort to comb the

unruly cowlick into respectability. Like the debutantes of eighteenth century

England who were conveyed to London for the ‘Season’, they are subsequently

paraded in frills and feathers in hope of procuring a marital/literary partner.

And there are a number to pick from, parading the dance floor: the ubiquitous

vanity presses, glamorously attired and available for a hefty price, the

literary agent who hovers on the peripheries, assessing each with a practiced

eye, and the haughty mien of the publishing giants who recline in the other room

(they seldom attend such gatherings). For those who seek a friendlier

reception, there are a promising number of small, independent presses who love

to dance. Ideally, the writer fills their dance card and in the process of an

enchanted evening decides upon the prospect best-suited. Of course that

particular ‘prospect’ must also concur (barring the vanity presses who will

obligingly embrace all and sundry) and the process itself is far from done. If

aforementioned progeny waltzes off into the sultry night with a fetching

literary agent, that agent must still convincingly sell the product to a

publishing house with a highly discerning economic nose. My point is, whether

the debutante is whisked away by an aristocratic Charming, of the male or

female variety, the wedding is still far off.

Once

the glow of evening festivities have subsided, regardless of whether a partner was

acquired or no, the writer must begin again, summoning all available neurons to

the task (however many have survived the onslaught of the previous year’s

‘Season’), confronting the blank page with a determined optimism and

vigor. For beginning is imbued with optimism, pregnant with the

possibility of all that is to come. And so it is that the wheel turns and the

literary cycle repeats itself, the new novel emerging like tender shoots of

green beneath the snowbank. The number of revolutions in the writing rotation

are defined by the human life span, providing the writer retains the requisite

stamina, focus, and sanguinity (although I am increasingly of the opinion that

writers are instinctively inclined – that they can no more cease to write than

they can forgo food – that the steady composition of sentences is a dogged

thing, perhaps even, at times, an unwilling thing). When deep in the throes of

such cyclical endeavors of unforeseen intensity and unknown duration, knowing

as one does that the literary offspring might not prove sufficiently alluring

to particular aristocratic publishing tastes, a writer might be forgiven for

thinking of their task as a Sisyphean one.

Sisyphus,

according to Greek tradition, was a fairly nasty fellow; as king of Ephyra, he

defied Zeus, seduced his niece, deceived Hades, and contrived to murder his

brother. His punishment for these transgressions consisted of pushing a weighty

boulder up a steep hill; the rock, enchanted, rolled away from Sisyphus just

prior to reaching the summit, consigning Sisyphus to an eternity of futile

labor and perpetual frustration. Interminable activities have since been

described as Sisyphean. This metaphor finds some similarity with the writing

task; while the endeavor seems a ceaseless one, I do not however presume to

liken my fellow scribes to such an unpalatable fellow, nor would I ever condemn

the vocation to the realms of futility.

Camus

in his philosophical essay, Myth of Sisyphus, offers an intriguing perspective. While

we strive to better understand the world, seeking to ascribe some measure of

meaning to the human endeavor, Camus would tell us (as is ominously proclaimed

above the gates to Hades): ‘Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.’ For the fiery

collision of this human quest for meaning with the quiet unfathomability of the

world results, according to Camusian doctrine, in a contradiction that results

in the absurd where true knowledge is impossible, where rationality and science

cannot reveal the impenetrable world, and “If the world were clear, art would

not exist.”

For

the artistic endeavor seeks to make sense of external things, to cast a glance

darkly across the murky expanse that so thwarts our understanding. But truth

eludes us and writers, according to Camus, are confined merely to the

conveyance of experience. And to achieve authentic absurdity, one must not only

abandon all hope, but refrain from even alluding to the possibility of such a

tantalizing carrot. But Camusian hope is a futile yearning for a resolution of

the prevailing contradiction. Camus does (reluctantly?) allow us a form of

contented acceptance once one acknowledges the certainty of one’s fate, the

futility of one’s task, and the concomitant realization of situational

absurdity. But one is not allowed to relinquish the endeavor, voluntarily slip

beneath the waves; one must ceaselessly confront the absurdity. Camus concludes: “The struggle itself […] is

enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

This statement is so

profound, with marvelous implications for the writing metaphor I am painfully

trying to explicate, that I must repeat it: ‘One must imagine Sisyphus happy.’

And this, for writers, is the answer!

One must befriend Sisyphus and love the rock. The journey is everything and if

your literary progeny turns out to be a bit of a wallflower, fret not! There

are, increasingly, a number of options for the dedicated writer; the important thing

is to find happiness in the process, in shoving one’s shoulder to the boulder

and hefting it uphill. For even if the rock is heavy and the path forbidding,

the view from the heights gladdens the heart and the ‘Season’ rolls around with

reliable regularity. And with each uphill foray, the muscles of leg and back

are strengthened, fortified and

increasingly equipped for the task; as is the case with each subsequent literary

work: our pen becomes ever more refined, our voice emphatically our own. And

how can one achieve this without the continuum of literary labor?

Post Script: And insofar as the

tantalizing carrot is concerned, unlike Camus I cannot entirely eschew hope.

For while the French philosopher laments our inability to find inherent meaning

in the understanding of everything, I find myself rather satisfied with

understanding a little bit. Can we not be content with incremental growth? To further our humble

comprehension in fits and starts by the variety of mechanisms open to us? Is there

not hope in this?