A writer acquaintance of mine was recently labeled as ‘forgotten’

and I find myself wondering what that means precisely. Forgotten by whom? By a

demographic that didn’t read him? For doubtless we each have our audience, the

readers whose sympathies and inclinations resonate with our own. And an even larger segment of society that

invariably find literary diversion in genres other than that which we labor upon. And being the

recipient of such aspersions (for an aspersion it surely is!) what does it mean? I admit to some defensiveness on

this individual’s behalf – knowing him to be an exquisitely literary writer in

two languages no less! A feat I could not even begin to comprehend myself. His

proficiency in this regard reminds me of Joseph Conrad’s literary virtuosity

and his enviable command of the English tongue that far outstripped many a native

speaker.

So. Back to the adjective, if I may. Forgotten. The last novel I devoured springs to mind – The Lost Estate. The author of this fine

literary work, Henri Alain-Fournier, tragically killed in the first world war, left his next

uncompleted. Given the glorious exposition

of the first, the unpublished, unfinished second remains a collective shame for the rest of the reading world, and a reminder of the horrific waste of human life (and all the potential that resided therein!) that World War One entailed. I am now

embarking upon the marvelous Bánffy trilogy – a series of novels that detail the enviable languor of the

Hungarian aristocracy prior to the assassination of Ferdinand – a trilogy

that has, only very recently, been translated into English. So it would,

indeed, be absurd to label Bánffy (or the relatively obscure Alain-Fournier) as ‘forgotten’ despite the fact that he was

seldom known outside of Hungarian or Romanian literary circles.

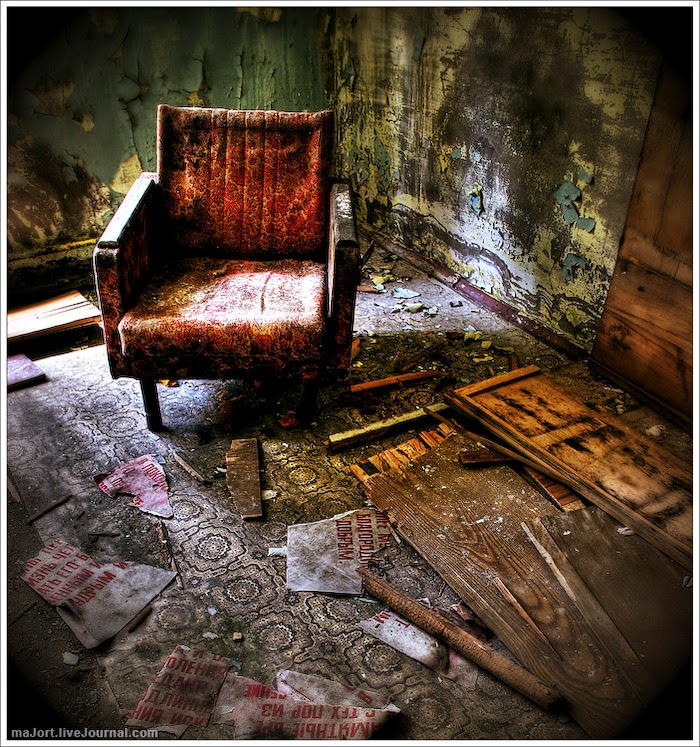

But, and I stand corrected, the notion 'forgotten' implies a previous awareness, something

that lingered in the faint dimness of memory but has since been extinguished.

Forgotten implies a lack of currency, a lack of contemporary attention, a

dearth of clamoring readership. And how precisely is this ascertained? For

readers tend to be the quiet sort, curling up beneath the lamp, novel in hand,

in the darkening of an evening – when the intrusive clamor of the day has

subsided, when children are a-bed (dreaming of sugar plums? For ‘tis the

season!) So who presumes to know what they are, and are not, reading?

For the thing is, even after many a marvelous writer has

shuffled off this mortal coil, they are still read – whether it be by readers however

few in number, or however linguistically specific. In this electronic age,

particularly, e-versions whip across the globe with unprecedented alacrity. I feel some degree of certainty in positing

that avid readers of Fifty Shades of Gray have little appreciation for Melville’s

lengthy asides on the nineteenth–century whaling industry, or the inclination

to wade through Hugo’s background on Parisian nunneries or Waterloo precursors.

I do not mean these statements to be genre-inflammatory

or to demean individual reading proclivities but simply reiterate the notion

that we, individually, seek out and read specific kinds of novels tailored to

our particular tastes. And the classic-lovers, those that yearn for the exquisite phrase (however lengthy the preceding), we

are in the minority – the literary lifeboat keeping Penguin Classics and Oxford

World Publishing afloat. Could one then postulate, perhaps, that Hugo and

Dickens, Dumas and Dostoyevsky, and Bánffy to boot, are ‘forgotten’ by contemporary readers of erotic fiction? Indubitably

they are not forgotten by those who appreciate their works, by those who seek

them out in preference to many others. But most of us have a passing acquaintance with these literary greats, do we not? Abusing Shakespearean prose in high school English class, or forced to wade through Dickens for a pass-worthy grade. Perhaps they linger on the fringes of memory for those who do not return to the classics as adults, perhaps less appealing later due to the coercive nature of earlier exposure? One did not, after all, have much of a choice if one wanted to pass English in high school; I remember the stilted renditions of Romeo and Juliet in eighth grade: "What light through yonder window breaks? It is the east, and Juliet is the sun!"

To be utterly candid (as I always strive to be in these

Humble Musings – for those who manage to make their way through them to the end

– I do apologize – undue verbosity has always been my failing!) I had never

even heard of Bánffy prior to a much-appreciated recommendation by Rosalind

Brackenbury (read her Becoming George Sand, it is marvelous!) And so while Bánffy was, and still is, unknown by many, his writing is no less diminished by the smaller circle of appreciation. In

fact, upon reading the first chapter, I promptly returned the kindly loaned copy

back to Rosalind and purchased a copy for myself, knowing that this was a

literary work I would want on my shelf for years to come. Pim Wiersinga’s novel

‘The Pavilion of Forgotten Concubines’ is another such literary wonder that

will be snugly situated next to these other works of narrative longevity.

I do not mean to be pugnacious. I am simply baffled as to what is meant by 'forgotten' in regards to a writer of great literary merit. Many of the beloved writers represented upon my groaning bookshelf might be said to be forgotten by the multitude - particularly given the resultant difficulty in acquiring their works - but they are dedicated artists to the literary phrase. Their works pay glorious tribute to what it means to be human. And if they are forgotten, then, like Spartacus, I too rise to my feet: "I am forgotten!" And indubitably another: "No, I am forgotten!" Until in resounding accord, the literary multitude cry out: "I am forgotten!" For after all, it is all about the agonized pursuit of literary perfection. And what a particular endeavor that is! What speaks to one, is mute to another. But we, as writers, pursue our calling to the grave. Until we are dust and bones. But the words will remain, however faded upon the page, or intermittent the virtual connection.